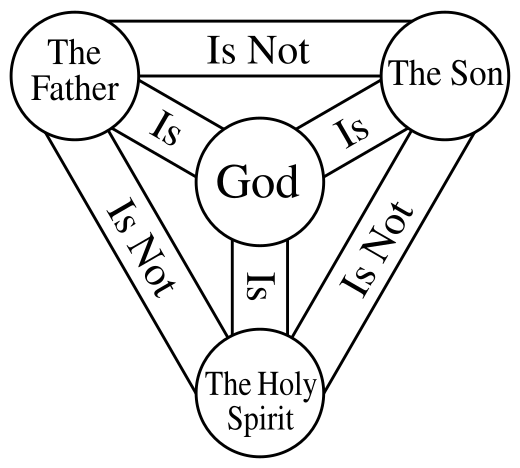

On "orthodox" Trinitarianism (OT), the Trinitarianism expounded by, e.g., the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church, the second person of the Trinity, the Son, is eternally begotten of the Father. That is, the Son stands in an asymmetric dyadic relation of being eternally begotten of the Father. However, OT also teaches that each of the three persons of the Trinity, including the Son, is absolutely perfect.

I believe that this is incoherent given the truth of certain extremely plausible metaphysical propositions. The following is my argument to this effect.

Stipulative Definitions and The Argument:

A perfect being = df. a being who has all perfections and lacks all imperfections.

Orthodox Trinitarianism = df. the Trinitarism held in common by Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and classical Protestants.

- (Suppose that) Orthodox Trinitarianism is true. [Assumption]

- If (1), then the Father is perfect, the Son is perfect, and the Holy Spirit is perfect. [definition]

- If (1), then the Son is eternally begotten of the Father. [definition]

- The Father is perfect, the Son is perfect, and the Holy Spirit is perfect. [1,2 --> E]

- The Son is perfect. [4 &E]

- The Son is eternally begotten of the Father. [1,3 --> E]

- If (6), then the Son is ontologically dependent on the Father for his existence. [prem]

- Therefore, the Son is ontologically dependent on the Father for his existence. [6,7 --> E]

- Every entity that is ontologically dependent on another entity for its existence is not perfect. [prem]

- Therefore, the Son is not perfect. [8,9]

- (5) contradicts (10); therefore, reject the assumption: It is not the case that Orthodox Trinitarianism is true.

This reductio ad absurdum argument contains only two premises that are not either definitions or merely follow from the logical rules of inference, viz., (7) and (9). I regard (9) as obviously true. Being such that one is ontologically independent is a perfection. I know that this is true by intuition, and in the same way I know that being unconditionally loving is a perfection -- it just obviously is. And so the complement of this property, viz., being ontologically dependent, is an imperfection. And any being that has an imperfection is by definition not perfect. Hence (9) is true. So what about (7)? Well, I also regard (7) as obviously true. Talk of being begotten makes no sense to me whatsoever if it doesn't imply ontological dependence. Indeed, if one reads the early church fathers, it seems clear that those who held that the Son was eternally begotten of the Father believed that he was ontologically dependent on him and that his point of origination was somehow in the Father. They believed in an ancient view called the Monarchy of the Father, wherein the Father is the supreme being and source of all reality. Everything -- including the Son and the Holy Spirit -- originates in the Father. Now, I don't have time to dig up quotes to prove this point, but suffice it to say interpreting "being eternally begotten of the father" to entail "being ontologically dependent on the Father" is a completely natural straightforward interpretation of this locution, and one that I believe was the view of the early church fathers. Modern theologians and Christian philosophers may try to say that such a locution doesn't imply ontological dependence, but only something like logical dependence, whatever that means. But quite honestly, I see these attempts as nothing more than ad hoc theological rationalizations. Orthodox Trinitarianism, and hence Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, etc., is simply incoherent given certain very plausible metaphysical assumptions.